Total laryngectomy patients have several options for regaining voice functioning. Ensuring best outcomes takes a team, explains Niels C. Kokot, MD, an otolaryngologist at the USC Head and Neck Center, part of the USC Caruso Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery.

One of the biggest challenges patients face after a total laryngectomy is a complete loss of voice. This experience often causes feelings of loneliness, anxiety and depression. Helping patients regain their voice functioning is a key part of the recovery process, says Niels C. Kokot, MD, an otolaryngologist with the USC Head and Neck Center, part of the USC Caruso Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery at Keck Medicine of USC.

Three years ago, Kokot performed a total laryngectomy on a 64-year-old woman from California who had advanced, aggressive laryngeal cancer. With about 12,300 new cases every year, laryngeal cancer is not exactly rare, but also not commonplace.

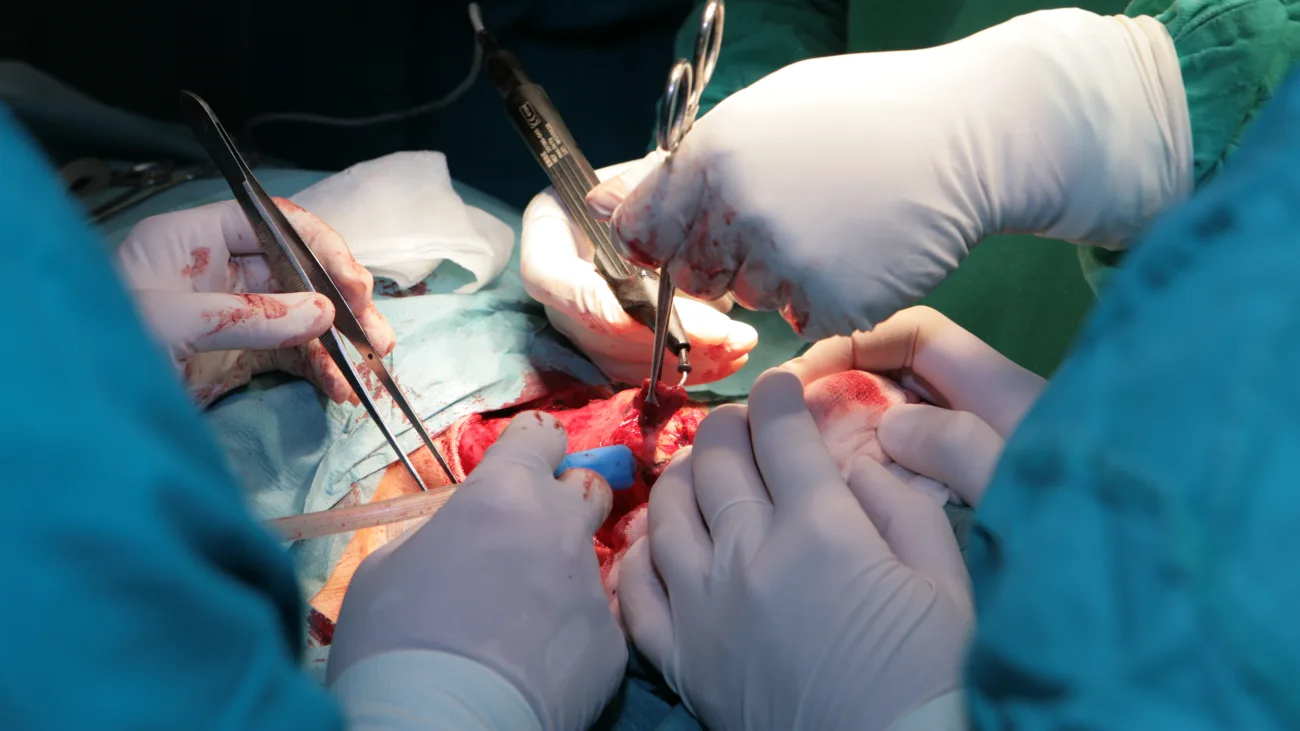

Finding that the patient’s laryngeal cancer had already spread to multiple lymph nodes and was destroying her voice box, Kokot performed a total laryngectomy – removing the entirety of the larynx. In addition to a total laryngectomy, the patient had reconstructive surgery on her throat and several months of chemotherapy and radiation.

Options for voice rehabilitation

Laryngeal cancer patients recovering from total laryngectomy must regain functions such as breathing and swallowing. Many also need microvascular reconstructive surgery after their tumor is removed to help with this process. Finally, they must also find new ways of speaking.

Several options exist to help patients regain their voice functioning after a total laryngectomy. One option is an electronic larynx, or electrolarynx. “An electrolarynx is an electric voice box that patients place on their neck,” Kokot explains. “It creates a vibration which manifests as sound.”

He points out, however, that some patients don’t like this option because of the electronic sound the electrolarynx creates. “It’s not a natural-sounding voice,” Kokot says.

Another alternative is esophageal speech. This technique requires the patient to learn how to swallow air and expel it to cause the throat to vibrate and produce sound. This process is very difficult to master, however, Kokot says.

The option that Kokot and his patient ultimately chose was tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) surgery coupled with a tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis. “We created an opening between the patient’s trachea and her esophagus and placed a one-way valve, or a tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis. When the patient breathes in and out, it forces air through the one-way valve, which creates a vibration in the back of the throat and, therefore, sound. That becomes the new voice.”

Kokot’s patient didn’t receive the tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis right away due to one particular complication: the COVID-19 pandemic. Because the patient’s total laryngectomy procedure and recovery took place during the height of the pandemic, her physicians decided to hold off on installing the prosthesis. Prosthesis installation often causes a lot of coughing, so the procedure was postponed to avoid aerosol exposure.

In the interim, the patient used an electrolarynx but ultimately discontinued using it once the prosthesis was in place. “She’s much more satisfied with the prosthesis,” Kokot says.

Specialized treatment

The path to voice rehabilitation is highly personal and must be tailored to each patient’s needs and to what a patient is most comfortable with, emphasizes Kokot, who specializes in treating cancers of the larynx and performing microvascular reconstructive surgery.

Total laryngectomy patients can develop new methods of speaking with support from a multidisciplinary team. Many patients choose to continue using a voice prosthesis long-term, and these specialists remain involved in a laryngectomy patient’s case throughout the road to recovery.

“We try to be as comprehensive as possible in treating our patients,” Kokot says of the USC Head and Neck Center team. For instance, head and neck surgeons perform reconstructive surgery and help patients overcome challenges with swallowing and voice restoration. Physical therapists manage ongoing tissue fibrosis complications resulting from surgery and radiation. Occupational therapists assist with lymphedema that laryngectomy patients often experience.

“And then there are ongoing needs for speech language pathology for managing the voice prosthesis,” Kokot says. “The speech pathologist teaches the patient how to use the prosthesis, because it does take coordination and practice to get a good voice.”

Life after total laryngectomy

Care teams can help total laryngectomy patients cope by preparing them in advance about what to expect post-procedure and during voice rehabilitation. Kokot’s patient exemplifies how multidisciplinary care contributes to a successful recovery after total laryngectomy.

“Given the extent of her disease and her high risk of recurrence, she has done remarkably well, not only from a functional standpoint but also the fact that it’s been more than three years and she’s likely to be cured of her cancer,” Kokot says.

USC Caruso Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery

At the USC Caruso Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, experts combine research with the latest technology to provide patients with the best care. As one of the nation’s most comprehensive otolaryngology programs, the team treats all conditions of the ear, nose and throat, including cancers and other tumors of the head and neck. We are recognized as one of the country’s top ear, nose and throat programs by U.S. News & World Report.

Topics